We are more than our Genes.

Traditionally we looked at our genes as if we got one set from mum and one from dad and that’s it, they’re set, and this is your limit for life.

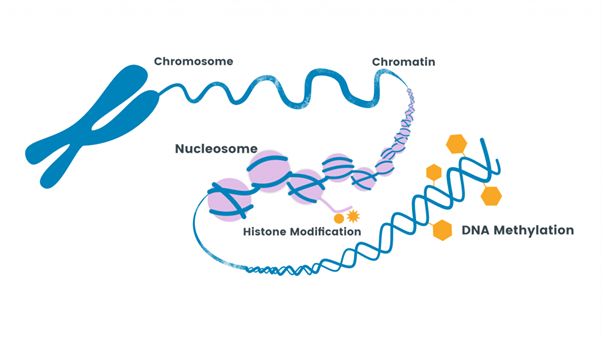

We now know that this is not the case, and it’s a new field of Epigenetics that really explains what happens.

Epigenetics says that we can alter our gene expression: meaning turn a gene on or off, through stimulus in or from our environment.

This expression is influenced in particular by diet and nutrition as well as by toxic load internally and from your environment, as well as thoughts and possibly your feeling/emotions.

The beauty of epigenetics is that it allows us as individuals to improve our lot in life and make the best of ourselves.

The evidence shows that we can enhance our health and wellbeing by our actions and choices. This can be seen in evidence showing that smoking has increased cancer risk. Not only for the obvious lung cancer but also in breast tissue. This was from a study on white female smokers with altered acetylation gene polymorphisms[i]. A polymorphism is a known variant of the gene in the population. Acetylation is a chemical tag applied to DNA to open it up to be transcribed. Other work demonstrates that stopping smoking lowers your cancer risk towards a non-smokers risk level, which means that today is a great day to stop smoking[ii]. This is a simple illustration showing that actions we choose affect our health outcomes.

Methylation is the process of tagging a gene with a CH3 (methyl group) so it can’t be expressed.

Methylation using nutrients like Vitamin B12, Folate B6 and S-Adenosyl Methionine (SAMe) to close off genes including those for tails, or horns and scale, let alone cancer or obesity.

Sadly, the understanding and control of epigenetics is not complete and while I’d like to be able to give you a B vitamin to increase methylation to turn off a specific gene it’s not that simple.

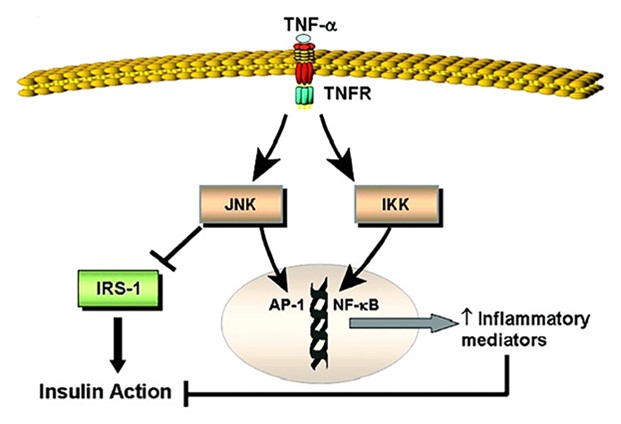

We know from twin studies that the environment you are raised in, including the choices of food and fluids we consume make a difference to DNA methylation[iii], therefore eating in a pattern close to the Mediterranean diet[iv] is found to have positive epigenetic effects and improved health outcomes including EEF2 methylation levels positively correlated with concentrations of TNF-α and CRP which are markers of inflammation and tissue damage.

Toxic exposure is also important. Known or suspected drivers behind epigenetic changes and ill health, can include heavy metals (Mercury lead and arsenic to name a few), pesticides (fly spray or glyphosates) , diesel exhaust, tobacco smoke, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (think BBQ food), hormones (the pill) , radioactivity, viruses, and bacteria. We can choose to use less plastics, filter water, eat organic, say no to drugs and control the non essential chemicals going in to us.

One of the big-ticket items that makes an impact on epigenetics and health is our thoughts and the amorphous word “stress”. A really cool paper in Rats that we can correlate in humans found he licking, grooming, and nursing methods that mother rats use with their pups can affect the long-term behaviour of their offspring, and those results can be tied to changes in DNA methylation and histone acetylation at a glucocorticoid receptor gene promoter in the pup’s hippocampus[v].

What this means is that nurturing and love and kindness early on in life had a positive downregulation in the stress response receptor in the brain. Sadly, the reverse is also demonstrated. However these effects were not shown to be set in stone, poor eating habits were shown to decrease the positive impacts of early life nurturing, and movement and exercise has been shown to help decrease early life negativity.

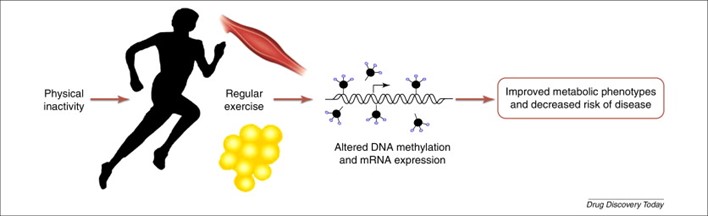

Exercise is another lever which we can alter our genome and live longer and healthier. Epigenetics finds that positive anabolic movement patterns and environmental stimuli early on (like playing sport as a kid) is associated with muscle memory later on in life and a greater likely hood of better aging and improved response to exercise as an aged adult. Conversely catabolic and low growth environments predispose to poorer muscle and aging outcomes[vi].

The point being that humans have genes that require movement to have health, which has important consequences, as sufficient quantity and quality of skeletal muscle are required not only to sustain performance in elite sport but also to enhance lifespan and promote health span into older age.

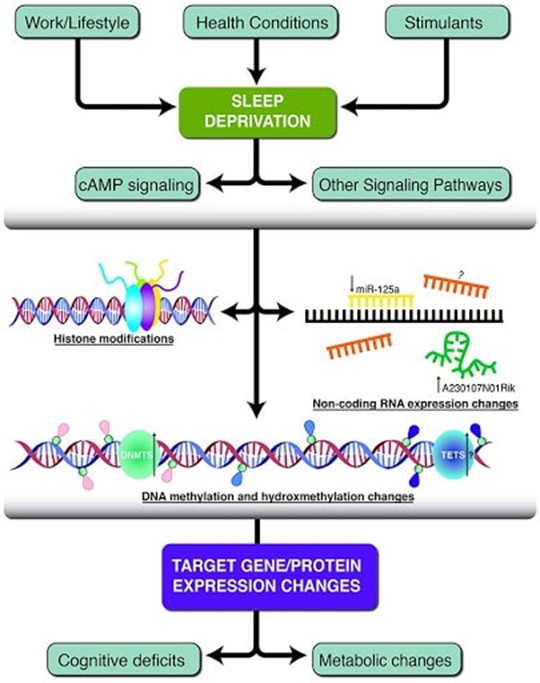

The final epigenetic lever we can control is sleep.

The effects of chronic sleep deprivation on hippocampal function have been extensively investigated using rodent models. The hippocampus is essential for memory consolidation and is involved with mood. A large body of evidence indicates that chronic sleep deprivation, sleep restriction, sleep fragmentation, or REM-specific sleep deprivation reduces adult Dentate Gyrus (DG) neurogenesis, disturbs hippocampal signalling pathways, impairs hippocampal synaptic plasticity, and disrupts the consolidation of hippocampal dependent memories.

Both acute and chronic sleep deprivation produce broad changes in epigenetic markers and patterns of gene transcription in rodents and humans. Of particular interest, depriving mice of sleep for 3 days down-regulates hippocampal CBP expression, reduces hippocampal histone acetylation levels at BDNF promoter regions, and weakens spatial memory. Interestingly current papers show that there are issues with consistently sleeping longer than 9 hours as an adult. We now know that sleep disorders such as snoring, and sleep apnoea have the ability to cause inheritable epigenetic changes[vii], which means that checking infant for tongue tie is important and being assessed for disordered breathing is imperative not only for yourself but to have healthy great grand children.

The long and short of it is if you don’t get enough quality sleep you lose your memory and your mind, can become depressed or anxious and won’t live long.

Over all our genes are not all that we are, we have the power to control much of our nonspecific epigenetics and influence our health and wellbeing down to the third generation. Choosing to eat well sleep well, exercise as well as be nurtured and nurturing is within our control. The environments we live in and choose for our future offspring all leaves a mark on our genes. Choose well and live long.

By Scott Wustenberg

[i] Ambrosone, C. B. (1996). Cigarette Smoking, N-Acetyltransferase 2 Genetic Polymorphisms, and Breast Cancer Risk. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 276(18), 1494. doi:10.1001/jama.1996.03540180050032

[ii] Tindle HA, Duncan MS, Greevy RA, et al. Lifetime smoking history and risk of lung cancer: results from the Framingham Heart Study. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(11):djy041. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy041.

[iii] Weinhold B. Epigenetics: the science of change. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(3):A160-A167. doi:10.1289/ehp.114-a160

[iv] Arpón, A., Riezu-Boj, J. I., Milagro, F. I., Marti, A., Razquin, C., Martínez-González, M. A., … Martínez, J. A. (2016). Adherence to Mediterranean diet is associated with methylation changes in inflammation-related genes in peripheral blood cells. Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry, 73(3), 445–455. doi:10.1007/s13105-017-0552-6

[v] Weinhold B. Epigenetics: the science of change. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114(3):A160-A167. doi:10.1289/ehp.114-a160

[vi] Does skeletal muscle have an ‘epi’‐memory? The role of epigenetics in nutritional programming, metabolic disease, aging and exercise

Adam P. Sharples Claire E. Stewart Robert A. Seaborne

Aging Cell (2016) 15, pp603–616

[vii] Morales-Lara, D., De-la-Peña, C. & Murillo-Rodríguez, E. Dad’s Snoring May Have Left Molecular Scars in Your DNA: the Emerging Role of Epigenetics in Sleep Disorders. Mol Neurobiol 55, 2713–2724 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-017-0409-6

Comments are closed.